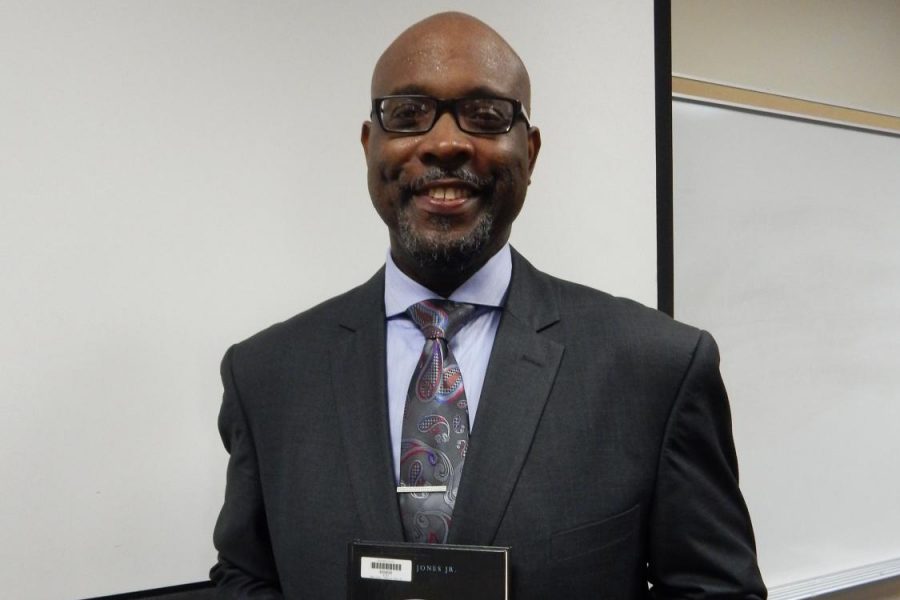

“Just Tell the Story:” Music Director Rufus Jones Paints the Life of Maestro Dean Dixon in Acclaimed 2015 Biography

Music Director Dr. Rufus Jones published his first autobiography in 2015, “Dean Dixon: Negro At Home, Maestro Abroad.” The acclaimed book told the story of trailblazing black orchestral conductor Dean Dixon.

May 17, 2021

It was 2009, and Music Director Dr. Rufus Jones was a professor at Georgetown University and paving his career as an orchestral conductor and educator. He was also deep in the research process of his first biography: that of Dean Dixon, the first black American to lead the New York Philharmonic and NBC Symphony orchestras in 1941.

Jones first discovered Dixon twenty years earlier in an article published in the February 1989 edition of Ebony magazine, which told the stories of twelve trailblazing black symphony conductors. Jones describes coming across the article as a serendipitous, but life-changing moment. Pursuing success in a primarily white-dominated field, Jones was no stranger to racism and prejudice himself, and found Dixon’s story to be an enormous source of inspiration.

“It’s important when you don’t see a lot of people in a profession that look like you to have someone you can be inspired by,” said Jones. “I appreciate [Dixon’s] sacrifice and how it made it more plausible for me to have a career. Despite all the obstacles this man had to face, he became one of the most respected orchestral conductors of the twentieth century.”

When Jones began further researching Dixon, he was surprised to discover that he had no full-length biography, and much of the existing information about him was riddled with inaccuracies. Jones decided to take on the task himself, first with a 2009 article published in the Journal of the Conductor’s Guild. He then continued his work into a nearly 200-page book titled Dean Dixon: Negro At Home, Maestro Abroad.

Jones wanted the book not only to demonstrate the challenges Dixon faced, but also his talents in the genre of classical music and his genius as an orchestral conductor. Yet another surprise arrived when Jones discovered a collection of Dixon’s personal effects and detailed documentation of his life at the Schomburg Center Library in Harlem, N.Y. Jones spent the summer of 2009 examining what grew to become thousands of papers and gathering the necessary information to compile his biography.

“It was really like putting together a puzzle,” recalled Jones. “I wanted for the book to read like a novel and paint all the important moments in [Dixon’s] life. In the end, I was writing in a way that I never thought I was capable of doing.”

Then, Jones made a decision that would become a critical part of the biography’s production: to contact Dixon’s wife and widow Ritha.

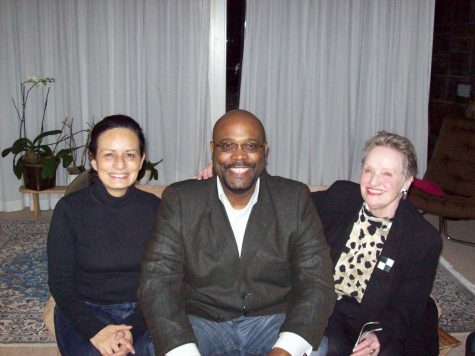

She invited him and his wife Felicia to visit her home in Switzerland, where they discussed his ideas for the biography, a concept about which the Dixon family had frequently been approached, but never seen completed. Jones promised the skeptical Ritha to fulfill her wish for a written legacy of her husband, and most importantly, to “just tell the story.” The quote became an epigraph credited to co-Pastor at Greater Mount Calvary Holy Church in Washington, D.C., Susie C. Owens, at the beginning of the novel.

After six years of writing, Jones presented the Dixon family with a finished draft of the biography, and chose to dedicate the book to Ritha.

“When Ritha saw the manuscript, she even helped me write the last chapter because I didn’t quite know how to end the story,” said Jones. “She really wanted this story to be told, and all I needed was that she was pleased. She passed away shortly after the book was published, but I think she was at peace.”

When Dean Dixon was published in 2015, Jones was met with responses of gratitude from some of Dixon’s most avid

European fans, as well as other successful black musicians and conductors that Jones lists in a special “On My Shoulders” section of the book. The biography has also received significant recognition, such as one of The New Yorker’s most notable music books of 2015.

“[Dean Dixon’s story] is still very relevant today, and people want to hear about how people have survived obstacles and succeeded as a result,” reflected Jones. “It’s an important story to tell on so many levels, from the musicianship of an orchestral conductor to the struggles of a black man.”

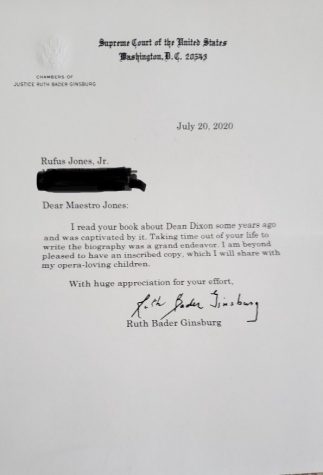

Another personal connection that came out of the biography occurred five years later in July 2020, when Jones decided to send an inscribed copy of the book to Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, notably a lover of classical music.

Jones mentions Ginsburg in the book as one of Dixon’s most appreciative listeners, as she even has spoken about meeting him in person as a child.

No more than two weeks later, Jones received a response written and signed by Ginsburg herself, describing her admiration of Dixon and his music, and her gratitude to Jones for telling his story. The letter harmonizes a framed copy of the original Ebony magazine article on a wall of Jones’ office today as symbols of pride and inspiration, reminding him of the obstacles and challenges that he and others have overcome to achieve success.