The Origin of Race in College Admissions and equal opportunity

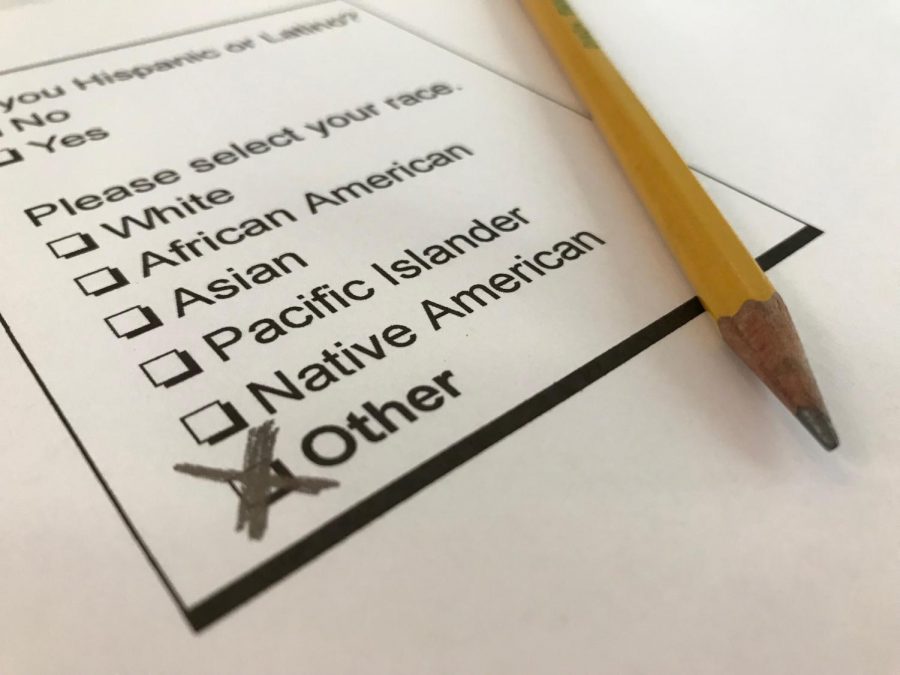

A student completes the race portion of a typical college application. Affirmative action in college admissions gives certain racially or financially disparaged students a leg up in the admissions process. However, sorting children into “racial bins” proved to be more problematic than helpful. Photo by Lara Russell-Lasalandra

April 30, 2019

Race has always been in the forefront of American social and political movements. Certain colleges joined the fight against racial injustice in the 1960s by setting quota systems, which required a percentage of admitted students to be a certain race. However, white male Allan Bakke challenged universities‚Äô rigid quota systems in the Supreme Court. Bakke claimed UC Davis declined his application solely on the basis of race since his test scores and GPA were higher than all of the admitted minorities. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Bakke stating that UC Davis‚Äô practices violated the equal protections clause of the fourteenth ¬Ýamendment and the Civil Rights Act. However, the use of race as a criterion in admissions decisions is constitutional.

Today, most selective colleges do in fact use race as a criterion in their admissions decisions. Obama-era guidance documents involving school admissions claimed that selective universities should “consider race to further the compelling interest of achieving diversity.” The modern college admissions is anything but colorblind.

Many argue that the problem with colleges admissions is not how they allow their applicants to express their race, but that they consider race at all. Many believe that colleges should solely focus on merit. However, merit-based arguments against affirmative action fail time and time again, most recently in Fisher v. University of Texas. UT’s considered race when admitting students with grades below the top 10% of their high school class. The court ruled the practice was constitutional.

According to an article on NPR, Asian-American applicants to Harvard undergrad “routinely perform better in academic and extracurricular ratings, but they consistently fall behind other ethnic groups in what is known as a ‘personal score.’”

“It’s an open secret in our community,” said the mother of Harvard student Jane Chen in an interview for NPR. “You have to work 10 times harder than other races to go to a top school.”

Applicants must define themselves with a checkmark. As students complete applications for undergraduate or graduate admissions, they receive the option to identify their race by selecting from an oversimplified items from a limited list of possible responses. With race being such a significant part of admissions, one would think that universities would give applicants ample opportunity to describe one‚Äôs racial background. However, they do not. Every applicant must neatly fit into a predetermined racial ‚Äúbin.‚Äù Unless applicants want to devote their entire personal essay to their racial background, they have nowhere other than a flawed demographics checklist to convey their racial identity. ¬Ý¬Ý

Senior Coven Blair struggled to display his Jamaican nationality in most of his college applications. He said that he selected ‚ÄúAfrican American‚Äù as his race when filling out the demographics section because almost all of the applications did not allow him to select Carribbean, Atlantic Islander, or something that would more accurately reveal his ethnic origins. Although he is black, Blair is not African. He takes great pride in his Jamaican heritage and feels he should be able to accurately depict where is family is from. ¬Ý¬Ý¬Ý

“I think that [colleges] should actually account for other types of black people because African Americans are not the only the black people who exist,” Blair said.

To remedy this problem, Blair suggests a rather simple solution. He said that colleges should “add more options” to the checklist to accommodate members of all races. Colleges might even consider making this question fill in the blank response, so students don’t feel obligated to conform to any one category.

According to a 2017 article from the New York Times, at the top 100 most selective universities, “black students who make up 15 percent of college-age Americans, made up just 6 percent of freshmen at these schools. For Hispanics, those numbers were 22 percent and 13 percent. Whites and Asians, meanwhile, were overrepresented.”

Even though minorities have made a lot of progress in advancing in American societies, ¬Ýthey still are not equal to their white counterparts. Affirmative action in universities may help give some minorities a chance at higher education. At the very least, race-conscious admissions allows schools to have a diverse student body that they wouldn‚Äôt have otherwise. Colleges should continue their affirmative action policies, as long as they provide students every opportunity to describe who they are.